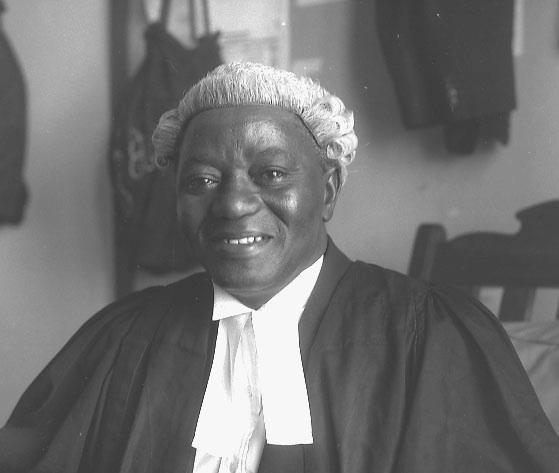

DR. JOSEPH KWAME KYERETWIE BOAKYE DANQUAH

Dr. Joseph Kwame Kyeretwie Boakye Danquah (December 21, 1895 – February 4, 1965), lawyer, scholar, author, and patriot, became the dean of Ghana’s politicians. He was a leader of the opposition to Kwame Nkrumah (q.v), president of Ghana from 1960-1966, but was arrested as a political prisoner and died miserably in a prison cell.

He was born at Bepong, in Kwawu, some 70 mi (112 km) west of Kumase, the son of Emmanuel Yaw Boakye Danquah, the chief state drummer of Nana Amoako Atta II, Omanhene (paramount chief) of Akyem Abuakwa, and of his father’s second wife, Lydia Okom Korantema, of the royal family of Kyebi, the capital of Akyem Abuakwa. He was educated in the Basel Mission elementary school at Kyebi, and then at the Basel Mission grammar school at Begoro in Akyem Abuakwa.

Leaving the school 1n 1912, he worked as a barrister’s clerk in Accra in 1913. From 1914-1915 he was a clerk at the Supreme Court of the Gold Coast. In 1915 he became secretary to his brother, Nana Ofori Atta I (q. v.), paramount chief of Akyem Abuakwa, as registrar of his tribunal. In 1916 he was appointed assistant secretary to the conference of paramount chiefs of the Eastern Province.

His brilliance as a student made his brother decide to send him to Britain in 1921 for higher education. He had already participated in local politics, first in 1916 as an organiser and as first secretary of the Akyem Abuakwa Scholars’ Union, and then in 1921 as the Akyem Abuakwa delegate to the Aborigines Rights Protection Society (A. R. P. S.) conference at Cape Coast.

He read philosophy and law at University College, London, and graduated B.A. in 1925, and L.L.B. in 1926, also being called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in the latter year. He had won the John Stuart Mill scholarship in the Philosophy of Mind and Logic in 1925, and was awarded his doctorate in philosophy at London University in 1927. He took an active part in students’ politics in Britain editing the West African Students’ Union magazine, W. A. S. U., in 1926, and becoming the union’s president.

Upon returning home to the Gold Coast in 1927, he declined the post of master at Achimota College, near Accra, and instead went into private law practice. He also plunged into politics, and was a foundation officer of the Gold Coast Youth Conference, which J. E. Casely Hayford (q. v.), the nationalist’ lawyer, had started in 1929 to help to bridge the gap between the intelligentsia and the chiefs. In 1931 he founded the Times of West Africa, which became the most popular Accra daily from 1931-1935. He also became the gadfly of the colonial administration, which blacklisted him, and read his mail from 1934 onwards. He campaigned against the Sedition Bill of 1934, which extended the definition of sedition, and the Waterworks Bill of the same year, which sought to shift responsibility for the costs of the water supply in the coastal cities from the government to the citizens. He was also secretary of the Gold Coast and Asante delegation which, in 1934, went to London to protest to the Secretary of State for the Colonies against the two bills. When the delegation’s mission failed, Danquah remained in England to work in the British Museum on his theory that the Akans of the Gold Coast were descendants of the people of ancient Ghana, the mediaeval empire which flourished between the 9th and 13th centuries. His research, although based on controversial evidence, led to the change of the country’s name to Ghana at the time of independence.

Upon his return home in 1936, he worked to reconcile the intelligentsia with the chiefs, reviving the Gold Coast Youth Conference in 1937, and leading a delegation from the conference to the Joint Provincial Council of Paramount Chiefs. This resulted in the formation of a united front of chiefs and people during the cocoa boycott of 1937-1938, in opposition to an attempt by 14 major firms to control prices. His advocacy of the farmers’ cause dates from this period. He wrote a number of popular political pamphlets, and became the idol of the youth. The Old Achimotans Association elected him to the Achimota College Council in 1939.

The Joint Provincial Council of Paramount Chiefs asked him in 1941 to prepare a memorandum on a new constitution, and in 1942 appointed him as their representative on a three-man committee, of which the other two members were Kobina Arku Korsah (q. v.), and Kojo Thompson, both barristers (attorneys), to draft a new constitution for the Gold Coast. The committee opted for a ministerial form of government, but its proposals were rejected by the British administration. In 1943, Danquah persuaded the Asantehene and the Asante Confederacy Council to accept a constitution which united Asante and the Colony into a single legislative council. The two councils – that of Asante and that of the Gold Coast Colony – presented a petition asking for this to the Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1943, and their request was reflected in the Burns Constitution of 1946. This was Danquah’s greatest diplomatic achievement.

He presented the Eastern Provincial Council on the 1946 Legislative Council, and with difficulty formed an elected members’ committee of the council, which he used to try to form a united front. In the Legislative Council, from 1946-1950, his advocacy of the cocoa farmers’ cause led to the establishment of the Cocoa Marketing Board in 1947. In 1946, Gold Coast farmers presented him with an illuminated address of commendation, calling him “The Farmers’ Lamp.” He pressed for various development projects, such as the Volta Dam, a university college, feeder roads in rural areas, improved sanitation, an adequate basic wage for workers, and the Africanisation of the civil service. But the ineffectiveness of indirect rule led him to press for self-government, and, in furtherance of this aim he, together with other nationalists, formed the United Gold Coast Convention (U.G.C.C.). The new party was inaugurated at Saltpond, on August 4, 1947.

Before the inauguration, he had offered the post of general secretary of the party to a young barrister, Ako Adjei, who had refused it, but who had suggested Kwame Nkrumah, who had been general secretary of the West African National Secretariat in London, and Joint-secretary of the Sixth (then called the fifth) Pan-African Congress, held in Manchester, England, in 1945 for the post. Danquah and other leaders agreed and sent Nkrumah, who was in London, £100 for his passage home. Nkrumah arrived back in the Gold Coast in December 1947.

When, in February 1948, riots broke out in Accra and other cities in protest against the cost of living and other grievances, following the shooting of ex-servicemen by a British policeman at a protest march, Danquah and the executive of the U.G.C.C. took advantage of the situation. They cabled the secretary of state for the colonies that the U.G.C.C. was ready to assume the duties of governing the country. Danquah also called upon the chiefs and the people of the Gold Coast to seize their freedom. A state of emergency was declared by the governor, and troops were flown in from Nigeria to crush the rioters. On March 13, Danquah, Nkrumah, and four members of the U.G.C.C. executive were detained by the governor. Tension rose, and the British government was forced to appoint the Watson Commission to enquire into the circumstances leading to the disturbances.

The six leaders were released, and Danquah came before the commission to demand self-government. The commission reported that a new constitution should be enacted to prepare the Gold Coast for self-government within ten years. It also described Danquah as the “doyen of Gold Coast politicians”.

When the Coussey Committee on Constitutional reform was appointed, Danquah became a member but Nkrumah was left out, and spent the period attacking his colleagues, alleging that they had accepted bribes from the British to delay self-government. On June 12, 1949 Nkrumah finally broke away from the U.G.C.C. to form his own party, the Convention People’s Party to demand “Self-Government Now”. When the Coussey Report was published in October 1949, Nkrumah attacked it, and threatened to declare a campaign of “Positive Action” for immediate self-government. Danquah opposed this but Nkrumah went ahead with his plan and was imprisoned.

After the general elections of February 8, 1951 held under the new 1951 constitution, Danquah entered the Gold Coast Parliament as the first rural member for Akyem Abuakwa. In the 1951-1954 parliament, he pressed for a constituent assembly to draw up an independence constitution. He had signed the minority report of the Coussey Committee advocating the exclusion of British ex-officio members from the cabinet, and pressed Nkrumah to demand complete Africanisation of the cabinet. He opposed hasty legislation, and examined the bills carefully. He attacked the colonial administration of Sir Charles Arden-Clarke (governor from 1949 until independence 1n 1957), maintaining that he was encouraging corruption in Nkrumah’s administration, which began in 1951, by refusing to appoint commissions of enquiry into the allegations of bribery and corruption. He never hesitated to write to the colonial administration on any national issue and his letters during the colonial period after independence are good historical source material and reveal a rare type of patriotism. He would write to British parliamentarians, journalists and ordinary citizens to correct wrong notions and to protest against false or misleading statements about the Gold Coast.

The U.G.C.C merged with the Ghana Congress Party in 1952, which combined with the Northern People’s Party (N. P. P.) to form the parliamentary opposition. But the C. P. P. was too strong, so the opposition did not make much headway. In the 1954 general elections, Danquah lost his seat, but continued his political activities afterwards. He received a United Nations Fellowship, and visited New York from November 1954 to February 1955. When he returned home, he joined the National Liberation Movement (N. L. M.) which had been formed in Asante to demand a federal constitution, and which was, through violence, challenging the C. P. P. effectively. But the N. L. M.’s stress on federalism made the movement suspect in the southern Gold Coast, and Danquah was accused of trying to break up the country. After two years of violence in politics, in which both sides suffered, a general election was held in 1956 to determine which party would lead the country to independence. The C. P. P. won the elections and Danquah again failed to win a seat.

On March 6, 1957, Danquah’s dream of an independent Ghana came true. But he had misgivings about the future of the country, and disliked Nkrumah’s attitude towards individual freedom and the rule of law. He opposed the arbitrary deportations which took place in 1957, and tried unsuccessfully to get the judiciary to stop them. In 1958, when Nkrumah proposed the Preventive Detention Act, Danquah wrote to ask him to withdraw it because it would begin a new age of barbarism. Nkrumah rejected his appeal. Danquah kept writing letters of protest to Nkrumah, attacking corruption in the government, and accusing Nkrumah of falsifying Ghana’s recent history. When the Preventive Detention Act was used against two opposition parliamentarians Danquah defended them, and carried the battle to the court of appeal. When the judges upheld the act, he attacked them for their lack of courage and foresight.

In 1957 the various opposition parties had merged to form the United Party, and in 1960 Danquah was nominated as the new party’s presidential candidate against Nkrumah. Though the odds were against him, and the government put great pressure on the electorate, he nevertheless received ten percent of the vote, and defeated Nkrumah in the Volta Region.

By 1961 Ghana had begun to face financial difficulties and Nkrumah was becoming attracted to the Soviet Union and the East. The budget of July 1961 led to social discontent, and was followed by strikes of railway men. Danquah and the United Party decided to take advantage of the situation to seek change of government by constitutional means. Nkrumah’s response was to detain Danquah from October 3, 1961 to June 22, 1962. He protested to Nkrumah from prison, and on his release carried on his fight for the rule of law and liberty of the subject by writing him several letters of protest. Nkrumah detained him again after the attempt on his (Nkrumah’s) life on January 2, 1964, because he had been mentioned as a possible president of Ghana.

Danquah was imprisoned on January 8, 1964, until February 4, 1965. He was treated brutally, and chained to the floor. He slept on the bare floor for months, and Nkrumah refused to allow him to be admitted to hospital when he suffered from asthma. He died of a heart attack on February 4, after writing four long letters of protest, of which Nkrumah took no notice. Despite the adverse political atmosphere of the day, he was given a hero’s burial in his hometown.

Joseph Boakye Danquah was one of Ghana’s most brilliant scholars. His Akan Laws and Customs (1928), Cases in Akan Law (1928), and his The Akan Doctrine of God (1944) reveal a scholarly and philosophic mind. He wrote extensively on Ghanaian languages, culture, and history, interspersed his writings with verse, and was a dramatist. He was the idol of the students at the University of Ghana, and a towering figure in the legal profession, in which his speciality was constitutional law and local laws and customs. Before his last detention, he was president of the Ghana Bar Association. He has won more friends and admirers after his death. In 1967 the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences established the J. B. Danquah Memorial Lectures to be delivered annually in February.

L. H. OFOSU-APPIAH