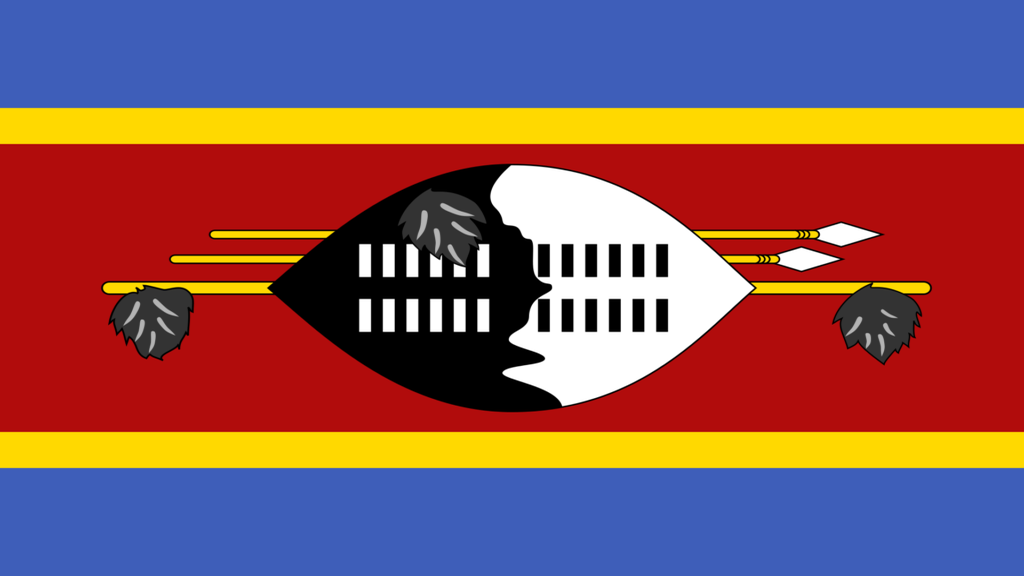

A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

The Kingdom of Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), the smallest of three former British High Commission Territories in southern Africa, is an independent state located almost entirely within the Republic of South Africa. With an area of 6,704 square miles (17,363 sq. km.), Eswatini is strategically located on the edge of the southeastern African plateau, lying between South Africa and Mozambique.

Its location has been a critical factor throughout its history; in early times Eswatini lay in the migration route of Bantu-speakers who were moving down from central to southern Africa. In the late 19th century it acted as a buffer between the Afrikaners (Boers) of the Transvaal and their access to the Indian Ocean through present-day Mozambique.

Eswatini was originally inhabited by the San (Bushmen) hunters and gatherers, who at one time roamed the southern African region. As Iron Age Bantu farmers moved down from Central Africa between 1200 A.D. and 1450, the San were forced to the west, to the less abundant lands of the Kalahari and the Namib deserts.

As a result of the Bantu migration, Sotho speakers once inhabited the area of present-day Eswatini. By the late 15th century, the Swazis, who are Nguni-speaking Bantus, had settled in southern Mozambique near present-day Maputo. Dlamini I, an Embo (or Bembo) Nguni, is considered to be the first leader of the Swazis as a people. (The Embo Nguni lived for several centuries between Delagoa Bay and the Lubombo mountains).

Other Nguni speakers were the Xhosa and the Zulus, who settled further south in Natal and in the Cape. The Swazis remained in Mozambique (Tsongaland) until the mid 1 700s when Swazi king Ngwane III suddenly moved his people out of their homeland on the plains and led them westward across the Lubombo mountains to the northern bank of the Pongola River. They settled there and built a capital at Lobama, which is revered today as the birthplace of the Swazi nation.

Ngwane III was succeeded by his son Gungunyane in 1780, and then by his grandson Sobhuza I in 1815. Both Gungunyane and Sobhuza were forceful leaders, a necessary attribute at a time when the southern African region was beset by ruthless men. Out of the chaos of the Mfecane (“Upheaval”) rose men like Dingiswayo of the Mathetwa, Zwide of the Ndwandwe, Moshoeshoe of the Basotho, Mzilikazi of the Ndebele, and Shaka of the Zulu.

To protect themselves during those violent times, Gungunyane formed the basis of what would become the Swazi army, which Sobhuza further trained and disciplined.

The Swazi army held its own during these turbulent times, and expanded the kingdom. Sobhuza was an astute leader. Rather than fight the Ndwandwe under Zwide, Sobhuza led his people north into west central Swaziland. They settled in the mountain region because it was healthier and easier to defend. The Swazis incorporated the Sotho and Nguni peoples already there, and in 1820 built a new capital.

When Sobhuza died he left his successor, Mswati II, a larger and more populous kingdom than he himself had inherited. In order to maintain control over the expanded kingdom, Mswati centralized control by instituting a nationwide system of age regiments.

Rather than owing their allegiance to individual chiefs or regional leaders, they would now owe their allegiance to the king. He set up a system of royal villages throughout the country to provide discipline and administration for the army and security for the king. Mswati’s reign was marked by violence. Outside the kingdom his armies ranged into the Transvaal, the Gaza state in southern Mozambique, and as far north as present-day Zimbabwe. Inside the kingdom, however, palace intrigues occurred, while the people had to endure occasional raids by the Zulu.

During Mswati’s reign the Swazis became one of the most powerful peoples in southern Africa. But on his death the authoritarian structure that he had devised collapsed. For the next ten years the Swazis fought each other over his succession.

Finally, in 1875, the fighting ended in compromise when Mbandzeni became king. Mbandzeni, however, was faced with a breakdown in internal order and with the threat of warring Zulus on his borders. To buy himself some time he formed an alliance with Europeans, but began a calamitous policy of granting mining and grazing concessions to Afrikaners from the Transvaal as well as to British land speculators.

Until 1890 Eswatini remained fairly independent, although its concessionary policies would bring it considerable dependence later on. In 1894 Britain and the Transvaal agreed between themselves that Eswatini would come under control of the Transvaal. But with the British annexation of the Transvaal at the conclusion of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902, all the rights and powers of the Transvaal passed to Britain.

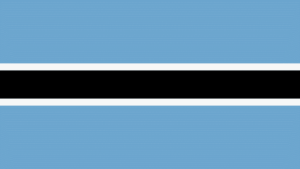

Eswatini continued to be administered by the governor of the Transvaal until 1906, when the power of administration was transferred to the office of the British High Commissioner for Basutoland, Bechuanaland, and Eswatini.

To sort out the confusion over overlapping concessionary claims, the British arbitrarily partitioned the land between

Swazis and concessionaires, with one third for the Swazis and two thirds for the concessionaires. Foreign commercial interests expropriated the best lands and eventually established irrigation systems, built up an economic infrastructure and, after World War II, developed a sugar and citrus industry for export. Enough timber was produced by the timber plantations to make timber the country’s second largest export item, after sugar.

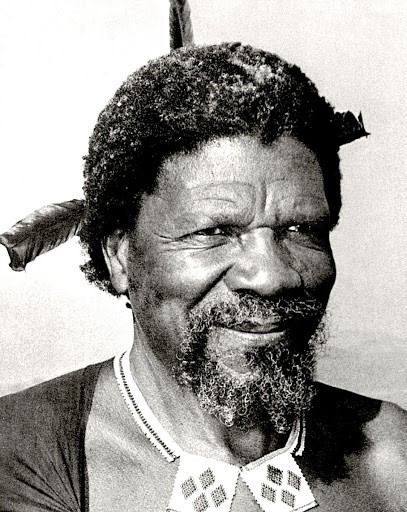

King Sobhuza II

When Sobhuza II took over the crown in 1921, he began legal proceedings to reclaim Swazi land from foreign interests. Most of the Swazi land has now been reclaimed and is now held communally as Swazi Nation Land. At independence in 1968, about 40 percent of the land was under Swazi control. The government has since slowly been regaining mineral concessions as well.

Even though the land is now being brought under Swazi control, foreign interests continue to dominate the economy. Sobhuza II encouraged foreign enterprises to develop the country’s mineral resources, such as asbestos, iron, and coal; he also offered tax incentives to foreign investors.

As a consequence, the modem sector produces 90 percent of the gross domestic product and employs 31 percent of the economically active population. Because there are more jobs in Eswatini, fewer Swazi men are forced to seek work in South Africa.

By 1977 the Swazi per capita gross domestic product was $580 per annum, the 12th highest in the World Bank ranking of African countries. Rural income, however was about 15 percent of the national average. Most Swazis continue to live in rural areas, the men often seeking employment away from the land in mines and sugar plantations.

1923 Swazi delegation to London (1923). let to right: (sitting} Benjamin Nxumalo, Mandanda Mtsefwa, King Sobhuza, Prince Msudvuka, Dr. P. kaSeme; (standing}AmosZwane, LozishinaHloph, Solomon Plaage (not a member of the delegation}.

Movement toward a participatory parliamentary system came slowly to Eswatini. As long as things were going smoothly for the royal house there was no movement toward universal suffrage or participatory democracy.

Since 1921 the interests of the white minority had been represented by the European Advisory Council (EAC). But when the Nationalist party came to power in South Africa in 1948, Britain realized Eswatini would be its own responsibility until it became independent. At the prompting of the British, who were anxious to be free of any economic responsibility for the territory, the Swazis developed their own court and treasury systems.

Events during the 1960s favored the movement toward independence. During 1962 and 1963 workers on the timber plantations and in the asbestos mines protested their working and pay conditions. They were poorly paid and provided with inadequate housing and poor food.

By May 1963 their local protests had developed into a nation-wide general strike led by Dumisa Dlamini, a leader of Dr. Ambrose Zwane’s Ngwange National Liberatory Congress (NNLC). The protests transcended the immediate concerns of the workers and condemned the vast disparities of wealth that the economic system had created. British troops sent in to quell the strikers were finally withdrawn in 1967.

In 1960 the Swazi Progressive party, originally formed by a wealthy, educated Swazi elite, supported a call by the EAC for an interim legislative

council, whose ultimate goal would be the creation of a Swazi constitution leading toward independence. Sobhuza concurred, and Britain agreed to set up a constitutional committee.

In London, British and Swazi representatives could not agree on who would control the country’s mineral rights, with the result that the constitutional conference of 1963 found itself deadlocked. In 1964, elections were held for an interim legislative council, and the Imbokodvo or Royalist party, in conjunction with the white United Swaziland Association, won the election.

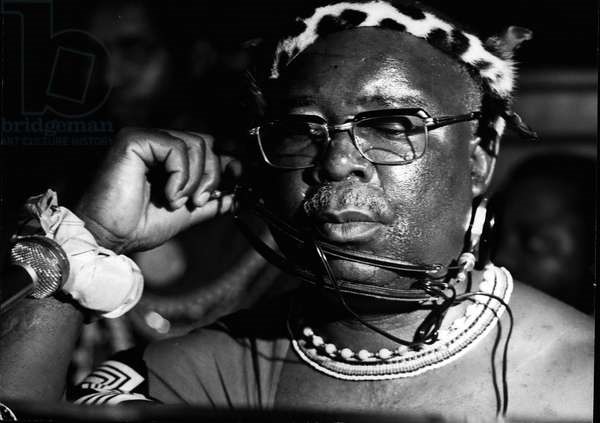

Prince Makhosini Dlamini (1914-1978)

The leader of the Imbokodvo, Prince Makhosini Dlamini, a member of the royal house, renounced white supporters and called for elections on the basis of one man, one vote. The legislative council then worked out a new constitution to provide a basis for independence. The new constitution was accepted, and elections were held.

In September 1968 the country became independent. Although whites thus lost political dominance, they continued to dominate the economic sector. At the time of independence, Prince Makhosini Dlamini became prime minister of the newly formed government.

In the 1972 parliamentary elections, the royal party lost three seats in the National Assembly.

Sobhuza II then abrogated the constitution and dissolved all political parties. He accepted support from the South African government to strengthen his 650-man army and, shortly before his death in 1982, also agreed to an unpopular land transfer. When Prime Minister Dlamini opposed the land transfer, he was ousted from the government and obliged to flee to South Africa. An heir to Sobhuza II was selected in a relatively peaceful transition, but on the understanding that he would not succeed until he came of age.

King Sobhuza II was the longest reigning monarch in Africa. He brought economic and political stability to his country of nearly 700,000 people. The Swazis are fortunate to have experienced long-term political stability. They are also fortunate to live in an area well endowed with rich fertile soils, rivers that run throughout the year, a healthy climate and a strong sense of nationhood through their cultural similarity and allegiance to the monarchy.

Eswatini has, however, remained dependent upon South Africa. It is a member of the Rand monetary area and most of its trade is with South Africa.