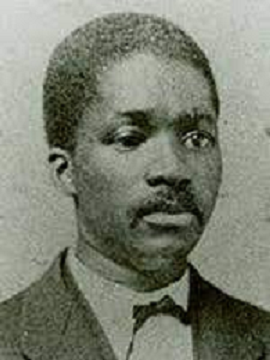

BARNABAS ROOT

Barnabas Root (1846-1877) was a Sherbro who received Western education at the Mende Mission school. He went on to study divinity in the United States and became one of a rare group of Africans who took up missionary posts among freedmen in the States.

Born in the Sherbro country, Barnabas was taken at the age of eight into the Mende Mission at the request of his father. (The Mende Mission supported by the American Missionary Association (A.M.A.) had been established in 1842 as a haven for famous Amistad mutineers. See SENGBE PIETH). The young lad proved to be an exceptional student and in 1850 he was chosen by one of the missionaries, John White, to accompany him on a visit to the United States. White had a dual purpose: Barnabas was an outstanding example of the success of the mission and his presence also enabled White to continue his study of the Sherbro language which he was turning into a written form. Audiences at missionary meetings throughout the Northern states were impressed by the young African’s command of the English language and his knowledge of the Bible.

Returning with White to Africa in 1860, Barnabas went on with his studies in the mission school and acted as interpreter for the mission until 1863, when he came to the United States to prepare for the ministry. He graduated in 1870 from Knox College at Galesburg, Illinois, with honours and received a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Chicago Theological Seminary in 1873. Reporting on the commencement exercises for Root’s class at the Seminary, the correspondent for Advance wrote that “The oration which showed the most thought and the finest culture was by a native of Africa, Mr.Barnabas Root.”

In 1873, Root was appointed pastor for a Congregational mission church for freedmen in Montgomery, Alabama. By accepting the appointment he became a member of a very small and distinctive group, native Africans who served as Christian missionaries in the United States. He was the second of such missionaries commissioned by the A.M.A., the first being Thomas DeSaliere Tucker (q.v.) also from the Sherbro country, who was appointed in 1862 to teach in a school for the freedmen on the eastern shore of Virginia.

During their time in the States, Root and Tucker had galling experiences of colour prejudice. In 1859, sitting with John White, Lewis Tappan, the treasurer of the A.M.A., and two white ladies at breakfast in a Chicago hotel, Barnabas was ordered to leave by the landlord, because some of the lady boarders refused to enter the dining room “while that black was there.” Tappan was incensed by the incident. Later, at Knox College, Barnabas displayed Christian forbearance with regard to racial prejudice. Writing to George Whipple, corresponding secretary of the A.M.A., in 1868, he said: “In regard to the influence and effect of the prevailing feeling of prejudice of which you desire an expression of my thought, it is a subject of which i have had much thought and feeling, but I fear I have looked too much if not altogether on the darkest side of the matter. I have felt it very keenly since i have been here… and I expressed myself freely about it… but I have asked God to show me my duty in this matter and to keep me a humble Christian from the blighting degrading feeling of self-abasement which I see in almost everyone of my race I meet in this country….One great cause of this feeling I think with many is unacquaintance with us or rather not being accustomed to come in daily and familiar contact with the blacks on the part of the whites….”

Root found his work among the freedmen rewarding, and felt that he had been able to help them. After a leave spent in New Orleans in the winter of 1873-74, where he hoped to recover from chronic throat ailment, he returned to Montgomery, adding the charge of a church in Selma to his existing duties. During this time, he also attended a meeting of the Congregational Association of Illinois, which led to the entire membership of the association boycotting a hotel operated by the Illinois Central Railroad because of its refusal to serve him a meal.

But his heart was not truly in the work in America. In 1868, he declared that he had given himself to God for the benefit of Africa, and from this resolution he never wavered. Accordingly, he returned to his homeland in 1874. Always frail in health, he was unable to readjust to the climate of Sierra Leone. Nonetheless, in the last three years of his life he established a new station of the Mende Mission, built a school house, revised a Mende dictionary, and began a translation of the Bible into Mende. He died in 1877.

CLIFTON H. JOHNSON